This is the third post in a series discussing where, how, and why tarot and fortunetelling show up as devices in literary fiction. In other words, they are an opportunity for a tarot-loving lit professor to indulge—with the ancient Sibyl’s permission, of course—two areas of passion and expertise. This week, we’ll be walking through Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell (2004). Be warned: spoilers await.

For returning series readers: Yes, the plan for a chronological literary journey has been wholeheartedly abandoned. This has nothing to do with my own inconstancy, of course. I write at the pleasure of Grande Dame Sibyl, and she was in a Napoleonic England kinda mood this week. As her scribe, I must follow orders.

The introduction to the “Fortunetelling & Fiction” series is available at this link: https://sibylslab.com/2025/06/06/fortunetelling-fiction-a-new-series-on-tarot-as-a-literary-device/. And should you want a comprehensive sense of the journey ahead, this is an evolving list of texts to be discussed in some serendipitous order of Sibyl’s choosing. (Previously reviewed texts bolded in red.)

- “The Waste Land” by T.S. Eliot (1922)

- The Greater Trumps by Charles Williams (1932)

- The Castle of Crossed Destinies by Italo Calvino (1973)

- Last Call by Tim Powers (1992)

- Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke (2004)

- Sepulchre by Kate Mosse (2007)

- The Tarot of Perfection by Rachel Pollack (2008)

- The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern (2011)

- Arcanum by Simon Morden (2014)

- The Devourers by Indra Das (2015)

- The Tarot Sequence by K.D. Edwards (2018)

- Ninth House by Leigh Bardugo (2019)

- The Midnight Bargain by C.L. Polk (2020)

- The Tarot Cafe Series by Sang-Sun Park (2002-06)

- The Raven Cycle Series by Maggie Stiefvater (2012-16)

- The Diviners Series by Libba Bray (2012-20)

Childermass & His “Cards of Marseilles”

Susanna Clarke’s monumental alternate history Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell incorporates tarot in a more peripheral but thematically significant way than something like Italo Calvino’s The Castle of Crossed Destinies. Set in 19th-century England during the Napoleonic Wars, the novel imagines a world where magic once existed but has long fallen into disuse until two magicians attempt to revive it. Clarke’s decision to weave tarot into this carefully constructed historical fantasy reflects her broader project of examining how power, knowledge, and tradition intersect in times of cultural transformation.

While tarot cards aren’t central to the main plot, they appear through the character of Childermass, Mr. Norrell’s servant, who uses a deck that he calls the “Cards of Marseilles” to divine information. (If you guessed that this is his Anglicization of the good ol’Tarot de Marseille, give yourself a gold star.) These readings provide crucial insights at key plot junctures and serve as counterpoints to the more academic magic practiced by the protagonists. Significantly, Childermass occupies a liminal position in the novel’s social hierarchy—neither gentleman nor common laborer—and his use of tarot reflects this in-between status. His divination serves as a bridge between the rarefied world of scholarly magic and the earthier traditions that persist among England’s working classes.

Clarke’s use of tarot highlights the class divisions in her magical world, but it also reveals the inadequacy of purely intellectual approaches to magic. Norrell’s bookish, respectable magic stands in contrast to the street magic represented by tarot cards. Yet repeatedly throughout the novel, it is Childermass’s cards that provide the practical guidance and warnings that Norrell’s extensive library cannot. This tension between institutional and intuitive knowledge forms one of the novel’s central conflicts, with tarot symbolizing magical traditions that have survived among common people despite the suppression of “proper” magic. The cards represent a form of knowledge that is embodied, practical, and accessible—qualities that the increasingly abstract and theoretical magic of the educated classes has lost.

The historical context of Clarke’s choice is equally significant. The early nineteenth century marked a period when tarot was transitioning from a card game to a tool of divination, largely through the influence of figures like Antoine Court de Gébelin and later, Éliphas Lévi. By having Childermass use the “Cards of Marseilles,” a deck born of Lévi’s and Gébelin’s French homeland, Clarke anchors her fantasy in real occult history while suggesting that such practices would naturally persist in a world where magic had once been commonplace.

The cards also connect to the novel’s exploration of prophecy and predestination, themes that resonate with the period’s anxieties about social change and national destiny. In Clarke’s world, magic is inextricably linked to fate—particularly through the enigmatic Raven King’s prophecy that haunts the narrative. Tarot readings become one manifestation of how destiny reveals itself, raising questions about whether characters are discovering their fates or creating them. This ambiguity reflects broader Romantic-era concerns about agency versus determinism, individual will versus historical forces.

The novel’s treatment of tarot ultimately serves Clarke’s larger critique of how societies preserve and transmit knowledge. In a world where the practice of magic has been largely relegated to dusty academic theories, tarot cards maintain a living connection to magical thinking. They represent not just divination, but a form of cultural memory—a way of preserving magical consciousness even when formal magical practice has been abandoned or forgotten.

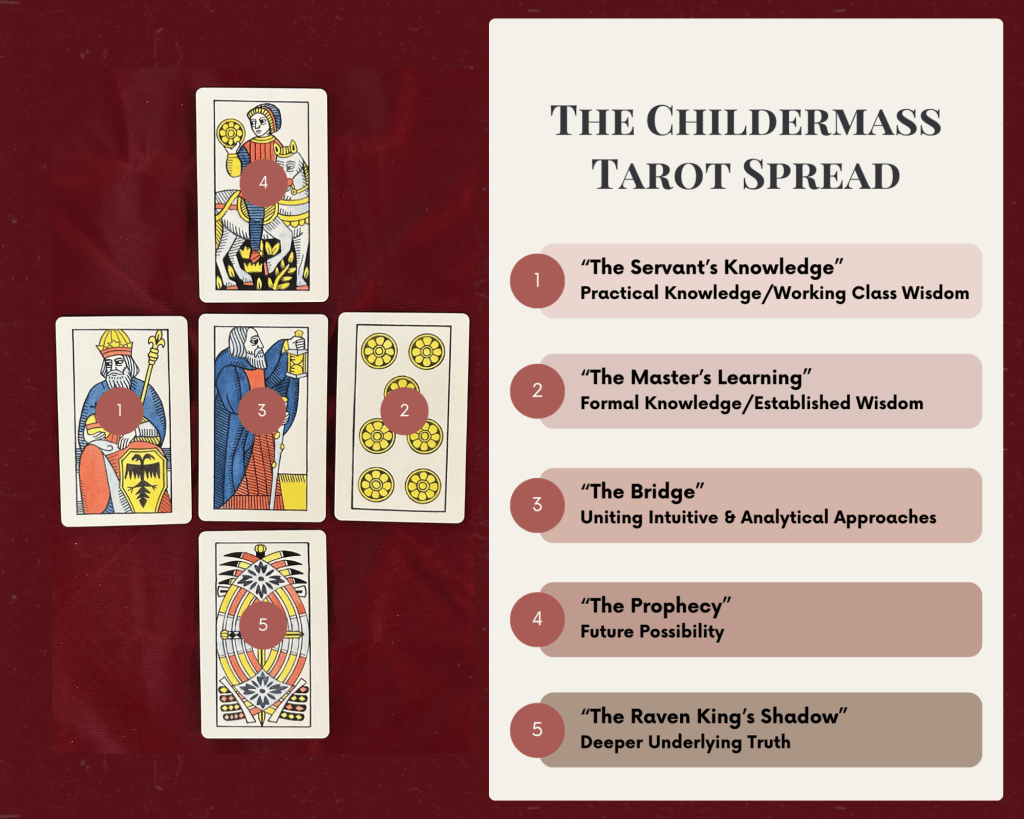

The Childermass Tarot Spread

Ready to do your own magic, Childermass-style? This is a spread that reflects the novel’s central themes of class, knowledge, and magical tradition. This five-card spread, named after the servant Childermass himself, explores the tension between institutional and intuitive wisdom.

Card Positions:

- The Servant’s Knowledge – What practical insight, or working class wisdom, am I overlooking?

- The Master’s Learning – What formal knowledge or established wisdom applies to my situation?

- The Bridge – How can I unite intuitive and analytical approaches?

- The Prophecy – What future possibility am I being called to recognize?

- The Raven King’s Shadow – What deeper, perhaps uncomfortable, truth underlies this entire situation?

This spread captures the novel’s exploration of how different forms of knowledge—embodied versus theoretical, common versus elite, intuitive versus scholarly—can complement rather than compete with each other. Like Childermass himself, the reading occupies a liminal space where multiple ways of knowing converge, offering guidance that neither pure intellect nor raw intuition could provide alone.

The spread also reflects Clarke’s historical moment, when tarot was emerging as a divinatory tool amid broader Romantic fascinations with folk wisdom, prophecy, and the supernatural. Each position asks the reader to consider not just what they know, but how they know it—and whose voices they might be excluding from their understanding.

Leave a comment