This is the second post in a series discussing where, how, and why tarot and fortunetelling show up as literary devices. In other words, they are an opportunity for a tarot-loving lit professor to indulge—with the ancient Sibyl’s permission, of course—two areas of passion and expertise. This week, we’ll be walking through Italo Calvino’s The Castle of Crossed Destinies (1973). Be warned: spoilers await.

For the introduction to this series, check out this link: https://sibylslab.com/2025/06/06/fortunetelling-fiction-a-new-series-on-tarot-as-a-literary-device/. The full list of texts, to be discussed in (roughly) chronological order, are:

- “The Waste Land” by T.S. Eliot (1922)

- The Greater Trumps by Charles Williams (1932)

- The Castle of Crossed Destinies by Italo Calvino (1973)

- Last Call by Tim Powers (1992)

- Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke (2004)

- Sepulchre by Kate Mosse (2007)

- The Tarot of Perfection by Rachel Pollack (2008)

- The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern (2011)

- Arcanum by Simon Morden (2014)

- The Devourers by Indra Das (2015)

- The Tarot Sequence by K.D. Edwards (2018)

- Ninth House by Leigh Bardugo (2019)

- The Midnight Bargain by C.L. Polk (2020)

- The Tarot Cafe Series by Sang-Sun Park (2002-06)

- The Raven Cycle Series by Maggie Stiefvater (2012-16)

- The Diviners Series by Libba Bray (2012-20)

Tarot as Tales in The Castle of Crossed Destinies

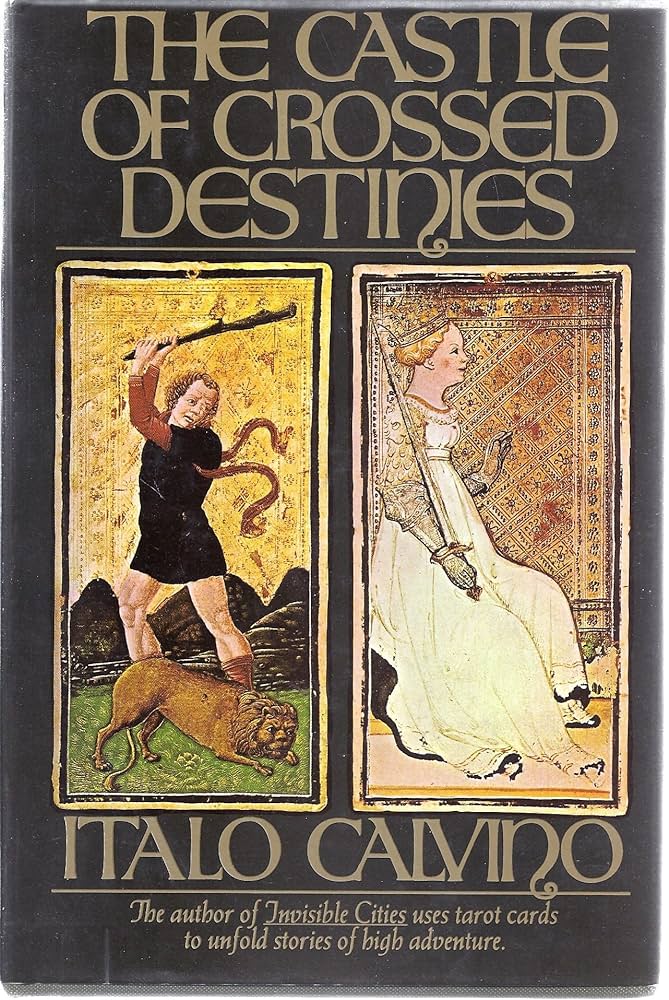

Perhaps no novel has integrated tarot more fundamentally into its structure than Italo Calvino’s experimental masterpiece, The Castle of Crossed Destinies. Published in 1973, this postmodern work uses tarot cards not merely as plot elements but as the primary narrative device, challenging conventional notions of both storytelling and textual authority.

In Calvino’s ingenious framework, travelers who have lost the ability to speak must communicate their stories using tarot cards. The narrator interprets these visual narratives, creating a complex tapestry of interwoven tales. Calvino actually used two different tarot decks as he composed the book: the Visconti-Sforza deck for “The Castle” section and the Marseille deck for “The Tavern” portion. This dual-deck approach reinforces the novel’s exploration of how different symbolic systems can generate entirely different narrative possibilities from the same structural foundation.

What makes this work so revolutionary is how Calvino transforms the tarot from a divination tool into a language system. The cards become hieroglyphs, pictograms that the characters must arrange to express their experiences. This approach highlights the multivalent nature of tarot imagery—how the same card can carry different meanings depending on context and interpretation. The Death card, for instance, might signify literal mortality in one story while representing transformation or the end of an era in another. This semantic flexibility mirrors the postmodern concern with the instability of meaning and the role of the reader in constructing significance.

The novel’s structural innovation extends beyond mere gimmickry to interrogate fundamental questions about narrative authority and interpretation. By removing speech from his characters, Calvino eliminates the traditional hierarchy between storyteller and audience. The narrator becomes less an omniscient voice than a fellow interpreter, struggling to decode the visual narratives laid out before him. This democratization of meaning-making reflects broader postmodern anxieties about objective truth and authoritative interpretation.

Furthermore, Calvino’s use of two distinct tarot traditions serves a deeper critical purpose. The aristocratic Visconti-Sforza deck, with its Renaissance artistry and noble imagery, generates stories of courtly romance and chivalric adventure. In contrast, the more populist Marseille deck produces earthier, more visceral narratives of tavern life and common experience. This juxtaposition suggests that our storytelling frameworks—our available symbolic vocabularies—inevitably shape the kinds of stories we can tell and the realities we can imagine.

The novel itself mirrors the tarot’s structure: fragmentary yet interconnected, open to multiple readings while maintaining internal coherence. Each story exists independently while contributing to a larger pattern, much like individual cards in a spread. Calvino doesn’t simply use tarot as a plot device; he transforms his entire narrative into a tarot reading, where meaning emerges from the juxtaposition of symbols rather than linear progression.

Perhaps most significantly, Calvino’s experiment reveals the tarot’s inherently literary nature. Long before his novel, tarot functioned as a storytelling system, with each card serving as a narrative prompt and each spread constructing a plot through symbolic association. By making this process explicit, “The Castle of Crossed Destinies” demonstrates how all narrative might be understood as a form of divination—an attempt to discover meaning through the arrangement of symbolic elements. In this reading, the novelist becomes a kind of fortune-teller, and every story an attempt to read the patterns hidden within the chaos of experience.

The Castle of Crossed Destinies Tarot Spread

Inspired by Italo Calvino’s “The Castle of Crossed Destinies”

This spread captures the essence of Calvino’s narrative structure—the intersection of multiple stories, the power of visual storytelling, and the idea that our destinies cross and influence each other in mysterious ways.

As you read the cards, bring the spirit of the novel with you. Like Calvino’s voiceless travelers, let the cards tell your story without words first. Notice the images, symbols, and connections between cards before consulting traditional meanings. Pay special attention to how cards 5 and 7 (your two paths) relate to the central position and final outcome.

Card Positions

1. The Arrival – Your current situation or the circumstances that brought you to this crossroads

2. What You Cannot Speak – Hidden influences or suppressed aspects affecting your path

3. The Heart of the Castle – The central theme or core issue you’re navigating

4. What Calls to You – Desires, goals, or destinations pulling you forward

5. The First Path – One possible direction and its potential outcomes

6. The Crossing Point – Where your story intersects with others; external influences

7. The Second Path – An alternative direction and its potential outcomes

8. The Other Traveler – What you can learn from another’s journey or perspective

9. The Tale Revealed – The deeper meaning of your story; synthesis and wisdom gained

Leave a comment