Sibyl strikes again, this time excavating the history of fortunetelling in the ancestral home of acolyte Amelia Joy. What is there to know about the story of divination as it emerges in her Irish roots? Well, for thousands of years, the misty landscapes of Ireland have been home to rich traditions of divination, from the ancient Druids to contemporary Celtic spirituality. Unlike the divination-averse Amish subculture of last week’s post, divination has remained woven into the cultural fabric of the Emerald Isle.

Druidic Origins

If we want to trace divination in Ireland back to its roots, we need to start with the Druids – those mysterious, white-robed figures who served as the priestly class of Celtic society. These weren’t just your average religious leaders. They were the complete package: judges, advisors, healers, teachers, and the essential bridge between the human world and the otherworld.

The Druids had a whole toolkit of divination methods at their disposal. They’d spend hours watching birds wheel across the sky, believing that flight patterns, behaviors, and even the types of birds that appeared could reveal messages from the gods. They were particularly attuned to oak trees and other sacred plants, reading omens in everything from unusual growth patterns to the way leaves fell in autumn.

Like many ancient cultures, they looked to the stars for guidance, tracking celestial movements with surprising accuracy given their tools. And they loved a good scrying session – gazing into reflective surfaces like still water, polished stones, or even dark pools of ink, waiting for visions to appear in the depths.

These divination practices weren’t just spiritual exercises – they had real-world consequences. Druids wielded enormous influence in pre-Christian Ireland, and their prophetic insights guided critical tribal decisions. Should the clan go to war? When was the best time to plant crops? Was this marriage alliance favorable? The Druids’ divinations often provided the answers that shaped the course of Celtic society.

Christian Transition and Syncretism

When Christianity arrived on Irish shores in the 5th century, with St. Patrick and his fellow missionaries leading the charge, you might expect that traditional divination practices would have been swiftly stamped out. After all, the Church wasn’t exactly enthusiastic about people seeking supernatural knowledge outside of approved religious channels – they viewed most forms of divination as pagan superstition at best and dangerous demonic practices at worst.

But the Irish, being the practical and adaptive people they’ve always been, found creative ways to keep their beloved divination traditions alive. Instead of an abrupt replacement of old ways with new, what emerged was a fascinating blend of both worlds – a true Irish solution to an Irish problem!

Holy wells provide a perfect example of this creative syncretism. These natural springs had long been sacred to Celtic deities and were places where people would go to receive visions and prophecies. Rather than abandoning these powerful sites, communities simply “converted” them, associating them with Christian saints instead of pagan gods. The divinatory practices continued much as before, but now with Christian prayers and symbols layered on top of the older rituals.

It’s as if the Irish people weren’t quite ready to give up their direct line to supernatural knowledge, even as they embraced the new faith. “We’ll take your saints and prayers,” they seemed to say, “but we’re keeping our magical wells and prophecies too, thank you very much!”

Samhain Divination: Peering Through the Veil

Samhain (pronounced “sow-in”) marked the Celtic New Year on October 31st and was considered the absolute best time for divination in the Irish calendar. Folks believed that on this special night, the boundary between our world and the Otherworld became thin enough to peek through, offering rare opportunities to glimpse future events and even chat with spirits.

While church officials might have been busy rebranding it as All Saints’ Eve, young people across Ireland were more concerned with using the magical potential of the night to get a sneak peek at their romantic futures. Who would they marry? What would their future spouse look like? The burning question for many a young heart.

Once tea became widely available in Ireland, it didn’t take long for people to discover that those leftover leaves at the bottom of the cup made perfect divination tools. Families would gather around the kitchen table as someone with “the gift” interpreted the patterns, revealing everything from upcoming visitors to potential windfalls or hardships.

Dreams, too, were taken incredibly seriously as portents and messages. A particular bird appearing in your dreams, the sensation of falling, or dreaming of a wedding – all these had specific meanings that could foretell weather changes, impending deaths, or fortunate events.

What all these practices share is the distinctly Irish concept of “thin places” – those special locations or moments when the veil between our ordinary world and the supernatural realm grows transparent enough to peek through. The Irish didn’t see divination as defying nature, but rather as tapping into a natural flow of knowledge that was always there, just waiting for the right circumstances to be accessed.

Agricultural Prognostication

Since most Irish families depended on farming for survival, figuring out what the coming year’s harvest would bring was incredibly important. On Samhain Eve, someone would carefully collect fresh eggs and crack them into water, watching intently as the whites spread into patterns. These delicate, ephemeral shapes were thought to contain coded messages about weather patterns and crop yields for the coming year.

Farmers also kept a close eye on their animals’ behavior during Samhain. If cattle seemed restless or agitated, that might spell trouble with storms in the coming months. But if the animals were peacefully dozing in their stalls? That was a good sign promising gentle weather and favorable conditions.

Communing with the Dead

As in many cultures, the Irish have a robust tradition of using the autumn season to commune with ancestors and spirits. Families would place an empty chair by the fire, sometimes with a plate of food nearby, as an open invitation for ancestral spirits to visit and share their wisdom through dreams or visions during the night. The truly courageous might even spend the entire night at fairy mounds or ancient burial sites.

There was also the curious practice of stone listening, where people would press their ears against standing stones at sacred sites, convinced that on this special night, the ancient rocks would actually whisper secrets about the year ahead. You can almost picture them there in the misty darkness, ears pressed to cold stone, straining to hear voices from another time.

It’s easy for us today to see these Samhain divination rituals as quaint superstitions or the precursors to modern Halloween games. But for the people practicing them, these weren’t just entertaining pastimes—they were serious business, approached with genuine reverence and even a touch of fear. The insights they believed they gained during this magical night would shape crucial decisions throughout the coming year, influencing everything from when to plant crops to whom to marry. Despite the Church’s best efforts to stamp out these “pagan” customs, they stubbornly hung on in Irish communities well into the 20th century. And if you look closely enough, you can still find some of these traditions continuing today in modified forms. The veil between past and present, it seems, remains just as thin as the one between this world and the next.

Tarot in Ireland: A Relatively Modern Addition

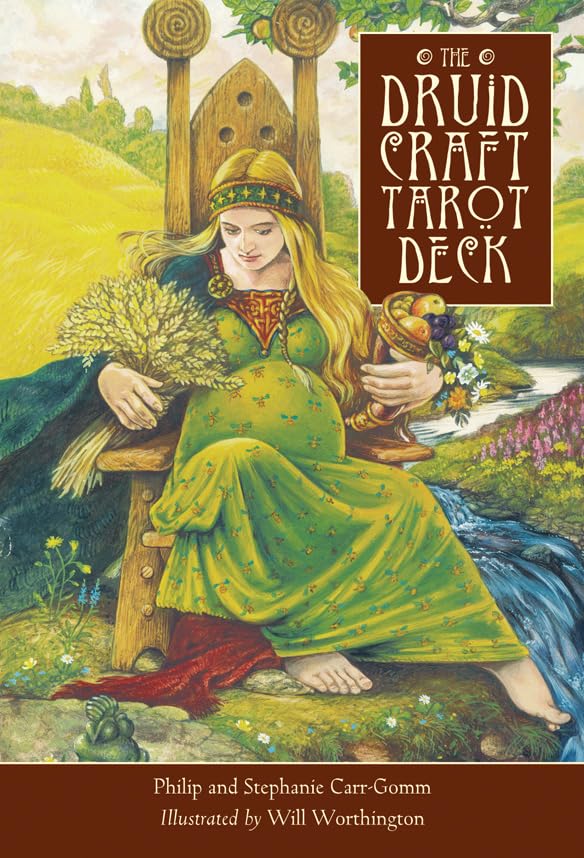

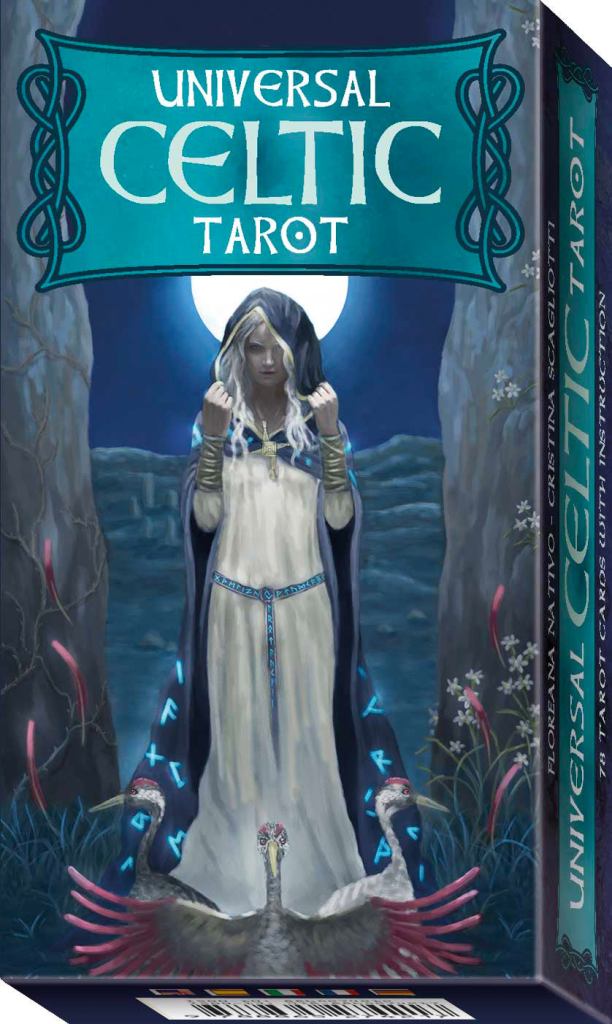

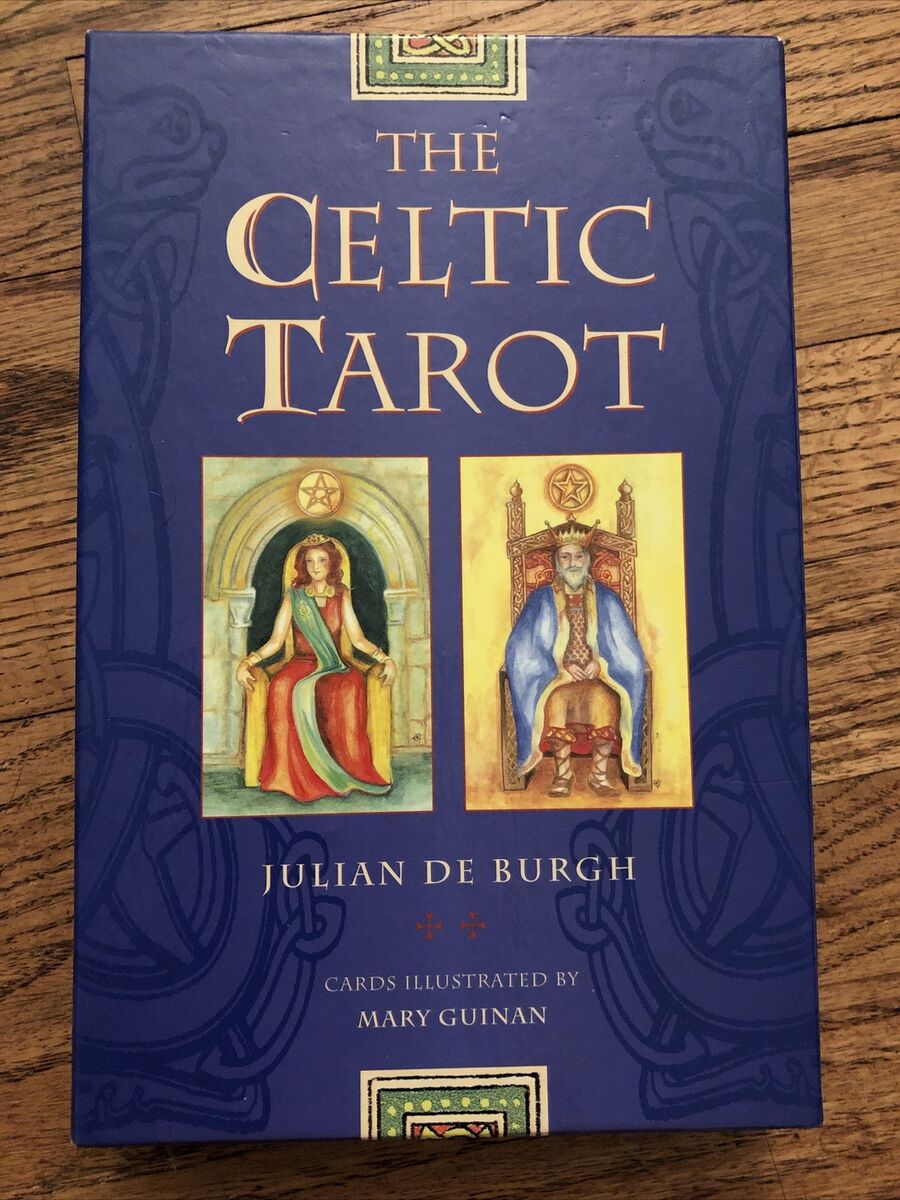

Interestingly, while Ireland has a rich history of divination practices, tarot cards aren’t actually native to Irish tradition. Unlike the ancient methods we’ve explored, tarot represents a relatively modern addition to Ireland’s divinatory landscape.

Tarot didn’t make its way from 15-century Italy to Ireland until the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Anglo-Irish gentry, with their continental connections, helped bring tarot to Irish shores, while the rise of occult societies like the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn introduced these mystical cards to interested circles. Irish literary figures, most notably W.B. Yeats, became fascinated with tarot symbolism and incorporated it into their work.

The Celtic Revival period from about 1880 to 1920 proved especially important for tarot’s integration into Irish divination traditions. During this time, the traditional tarot imagery began to be reimagined with Celtic symbols and mythology. Prominent Irish literary figures, particularly Yeats (who was deeply involved in the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn), helped legitimize tarot as a serious practice worth attention. What’s fascinating is how tarot reading started to blend with elements of traditional Irish fortune-telling, creating something uniquely Irish in the process.

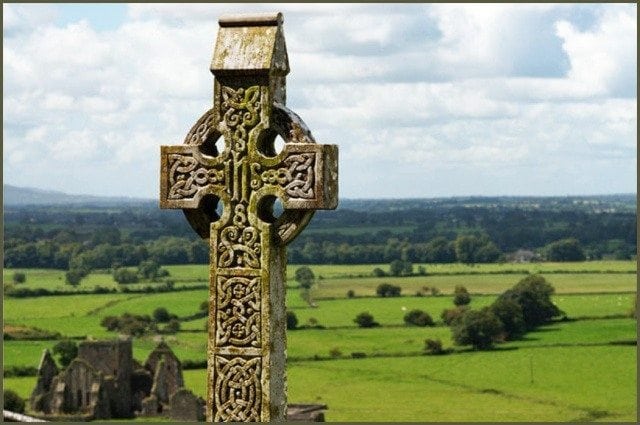

The real game-changer in Irish tarot history came with the creation of specifically Celtic-themed tarot decks in the mid-to-late 20th century. These innovative decks replaced the traditional imagery with figures from Celtic mythology and incorporated distinctly Irish elements like the Celtic cross, triskele, and spiral patterns. They featured sacred Irish sites like Newgrange and the Hill of Tara, and cleverly drew connections between the tarot’s Major Arcana and characters from Irish mythological cycles. It was a perfect marriage of an imported divination system with Ireland’s rich symbolic heritage.

Preserving a Living Tradition

What makes Irish divination so remarkable isn’t just its colorful history or unique methods – it’s the fact that these practices represent an unbroken thread stretching back thousands of years. Despite everything thrown at them – from Christian conversion to English colonization to modern skepticism – these traditions have refused to die out. They’ve changed, adapted, gone underground when necessary, and resurfaced in new forms, but the essential spirit has remained.

When you watch someone reading tea leaves in a cottage in County Kerry today, you’re witnessing something that connects directly back to the Druids who once interpreted bird flight patterns for ancient Celtic chieftains. The methods may have evolved, but several core elements remain strikingly consistent across the centuries: the deep connection to the Irish landscape, the understanding of time as cyclical rather than linear, and the fundamental belief that knowledge can flow to us through channels beyond our ordinary five senses.

As that wonderfully apt old Irish saying reminds us: “The past is never dead; it’s not even past.” Nowhere does this ring more true than in Ireland’s enduring, evolving relationship with the ancient art of divination. In a country where the past and present so often seem to exist simultaneously, perhaps it’s no surprise that the future can sometimes be glimpsed before it arrives.

Leave a comment