Yet again, Grand High Witch Sibyl has accommodated my curiosity about divination as it emerges across my ancestral landscape. This week brings us to my maternal roots, the Amish, a dogmatic community rooted in Christian orthodoxy that would characterize fortunetelling as, at best, an act of mystical hubris and (more likely), at worst, counter-biblical witchcraft that merits the highest form of community exclusion and punishment. But millennia of cross-cultural human history would suggest that humans have an inherent affinity for mysticism, superstitions, and folk magic, even when the framework of a culture requires that these exist by some other name. According to Sibyl, divination by any other name is still divination.

The Amish Worldview: Faith, Community, and Ordnung

To understand the Amish perspective on divination, we need to dive into what makes their faith and lifestyle tick. The Amish are Anabaptists – descendants of the 16th-century Radical Reformation – who believe in adult baptism, pacifism, and keeping church and state separate. Their communities live by the Ordnung, an scripturally-based set of rules that varies between settlements but always emphasizes humility, putting community before self, and submitting to God’s will.

Amish Christianity is highly practical. Instead of getting lost in complex theology, they focus on living their faith through everyday actions. They don’t worship in fancy churches – services happen in homes, conducted in High German and Pennsylvania Dutch, with long sermons about obeying God and upholding community values.

At the heart of everything Amish is this concept called Gelassenheit – it’s a German word that basically means surrendering yourself, yielding to God’s plan, and putting your community’s needs above your own desires. This principle shapes everything from their plain clothes to why they pass on modern conveniences, and it’s key to understanding how they view practices like divination.

Biblical Foundations: The Amish View on Divination

So what do the Amish actually think about divination? Like many Christians, they look straight to the Bible for answers. And the Bible doesn’t mince words when it comes to fortune-telling and similar practices.

Take Deuteronomy 18:10-12, which basically says: “Don’t engage in child sacrifice, divination, sorcery, witchcraft, or necromancy. God finds them wholly detestable.” And Leviticus keeps it simple with: “Don’t practice divination or seek omens.”

This particular prohibition stands alongside a number of more readily forgotten ones, including unequivocal instructions to avoid pork and beard-trimming. But I digress.

For the Amish, pigs and facial hair notwithstanding, most of the directives—and certainly those around divination—aren’t just suggestions, they’re direct commands from God. Since they take the Bible literally, any attempt to peek into the future or get supernatural knowledge outside of God’s revealed will is flat-out sinful. In their eyes, divination is trying to go around God’s authority and mess with His plan – which totally contradicts that Gelassenheit principle we just talked about.

Folk Practices and the Complexity of Tradition

Despite officially rejecting divination, the historical reality of Amish and Pennsylvania Dutch culture is way more complicated. Like many farming communities throughout history, early Amish settlers developed folk practices that sometimes blurred the lines between practical wisdom and superstition.

Take “powwowing” (or Brauche in Pennsylvania Dutch)—a folk healing tradition with European magical roots that took hold in some Amish communities. While it’s mainly about healing rather than fortune-telling, some aspects definitely venture into what we’d call magical thinking today—things like charms, special words, and symbolic actions to cure sickness.

Weather prediction through natural signs is another gray area. Some traditional methods—like watching how animals behave before a storm—are actually scientifically sound. But others—like predicting winter’s severity by checking onion skin thickness—edge into superstitious territory. Likewise, some Amish farmers still plant by moon phases too. Is that astrological divination? Many Amish don’t see it that way—to them, it’s just practical wisdom handed down through generations.

Practical Wisdom vs. Forbidden Divination

So how do the Amish make sense of these contradictions? It all comes down to intention and framing. Practices understood as accumulated wisdom based on generations of observation—like noticing certain cloud patterns before rain—are generally fine. These are seen as recognizing God’s natural order, not trying to uncover hidden knowledge.

But practices specifically aimed at revealing secrets, predicting personal futures, or gaining supernatural insights? Those get rejected as trying to bypass God’s authority. It’s about the heart’s intention as much as the action itself.

The Amish also distinguish between practices that acknowledge God is in charge versus those challenging His authority. Weather prediction based on nature is just recognizing patterns God created, while visiting a fortune teller is seeking knowledge God deliberately kept hidden.

Generational Changes and Community Variations

It’s worth noting that the Amish aren’t all the same. Attitudes toward these folk practices vary hugely between different communities and generations. The super-conservative Old Order Amish (from which my own family hails) tend to reject anything remotely resembling divination or superstition, while more progressive communities might tolerate certain traditions as cultural heritage rather than religious practice.

Younger Amish folks are generally less likely to keep up folk traditions that might seem superstitious. As education levels have risen and they’ve had more (limited) contact with the outside world, some of the weirder folk practices have faded away.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re getting more liberal about divination itself. Often, dropping these folk practices actually represents a purification of faith—moving toward a more Bible-based understanding that rejects both mainstream fortune-telling and traditional practices with supernatural vibes.

The Paradox of Predestination and Free Will

There’s an interesting tension in how the Amish think about the future. While they reject divination as trying to know stuff God hasn’t revealed, their theology includes elements of predestination—the belief that God has already planned out events and salvation.

This creates a complex relationship with fate. On one hand, they believe strongly in God’s sovereignty and plan; on the other, they emphasize human responsibility and the importance of choosing to follow God’s will. Divination is rejected not because the future is undetermined, but because knowing it is God’s business, not ours.

You’ll hear this in how they talk. Amish people often add “Lord willing” (or “Wann der Herr will” in Pennsylvania Dutch) when discussing future plans. This habit shows their deep belief that while we humans make plans, the future ultimately belongs to God—making divination both pointless and inappropriate.

The Outside World’s Fascination and Misunderstanding

As with any generationally resilient, culturally conspicuous, socially separatist demographic, mainstream culture is weirdly fascinated with the Amish and often gets their spiritual practices completely wrong. Popular culture sometimes portrays the Amish as mysterious or even magical, projecting qualities that have more to do with outsider fantasies than Amish reality.

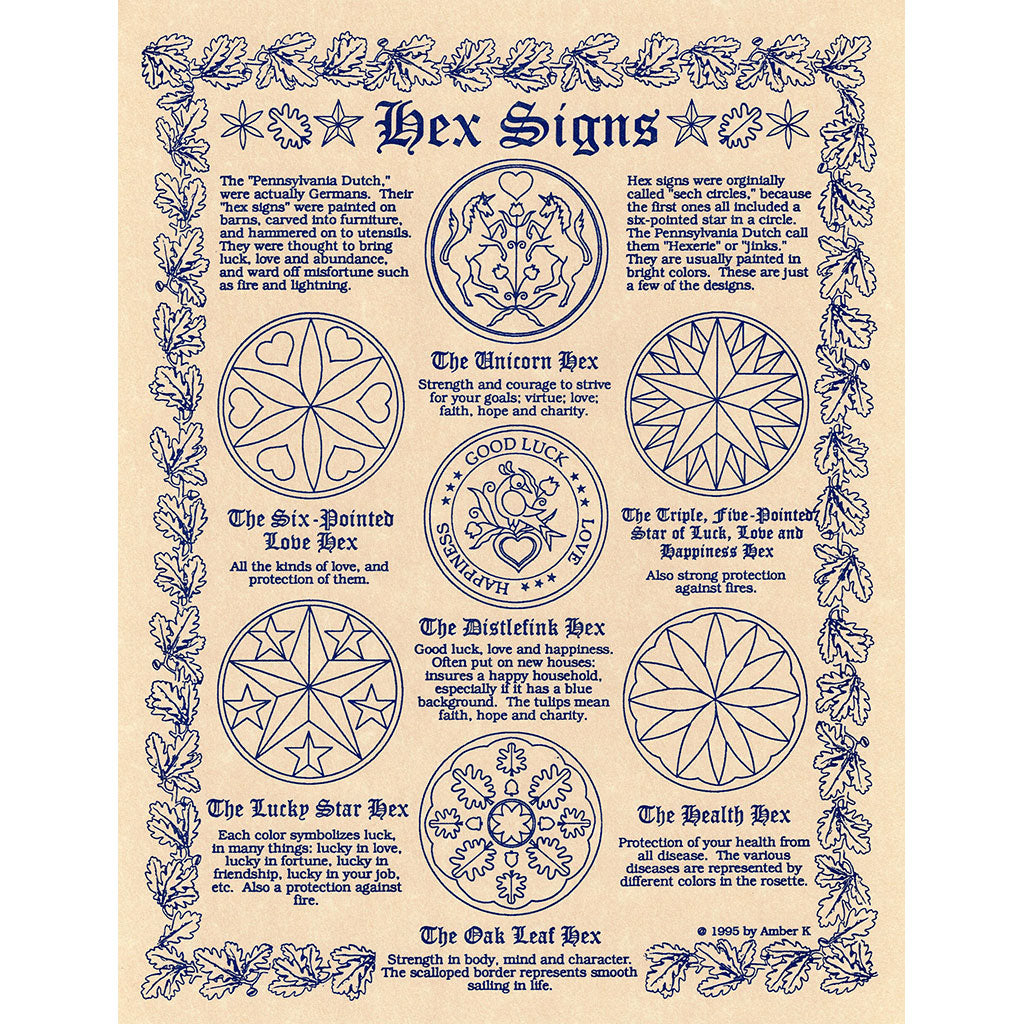

One persistent myth is that the Amish practice “hex magic,” particularly through those colorful barn decorations known as hex signs. In reality, these decorations are mainly found among non-Amish Pennsylvania Dutch folks, not the Amish themselves, who generally avoid decorative elements that might seem prideful.

Similarly, portraying Amish folk healing as mystical or magical misunderstands its context. Where such practices exist, practitioners generally see them as working through God’s established natural order rather than through occult means. The mysticism infused within some healing practices certainly merits examination for its classification, or not, as something that might be called folk magic. However, the nuance associated with this conversation rarely makes its way into a more fetishizing and dismissive representation of The Amish.

Faith in the Unseen Future

Perhaps the most profound aspect of the Amish rejection of divination is how comfortable they are with mystery and the unknown. In a mainstream culture obsessed with data, prediction, and control, the Amish embrace of divine mystery offers a pretty radical alternative. The Amish acceptance that some things just aren’t for humans to know—and that this limitation isn’t a problem to solve but a boundary to respect—stands in stark contrast to contemporary society’s drive to predict and control every aspect of life.

This comfort with mystery extends beyond the future to the complexities of the present. Rather than trying to analyze and categorize every experience, the Amish emphasis on practical faith encourages living fully in the present moment, trusting God with both the unknown future and the sometimes confusing present.

The Amish relationship with divination reveals a lot about their broader worldview—one that values faith over certainty, community wisdom over individual insight, and divine authority over human curiosity. Their rejection of traditional fortune-telling and other predictive practices isn’t about fear or ignorance but comes from a coherent theological framework that sees human limitations as central to spiritual wisdom.

Conclusion: Biblical Judgment & Holy Surrender

The Amish indictment of fortunetelling will be anathema to most friends of Sibyl. The appeal to biblical orthodoxy and dogmatic rejection of divination smacks of the sort of a judgmental conservatism that leaves little room for a fortunetellers’ kinship or sympathies. Speaking from my own ancestral sentimentality, I can assure you that, between my brown skin and my enthusiasm for divination, not even my own Amish maternal credentials are getting me into any farmhouses or church meetings. In fact, that a born-and-bred Amish woman produced the mess that is me–what they would undoubtedly consider a godless, elitist, woo woo Catholic–would probably be the highest mark against me. After all, with my mother’s Ordnung training and my own Amish roots, shouldn’t I know better? My eternal soul is in a sad state of affairs, indeed.

However, it is my own resistance to hubris that leaves room for another point-of-view. There’s a case to be made that the Amish rejection of future-telling isn’t regressive, but is instead a form of social resistance to a prevailingly normalized, and often poisonous, desire to control and shape outcomes. From this view, their culture of holy surrender could be considered among the most mystical of acts.

~Danielle, Amish-descended handmaiden of Sibyl Herself

Leave a comment